Research and Publications

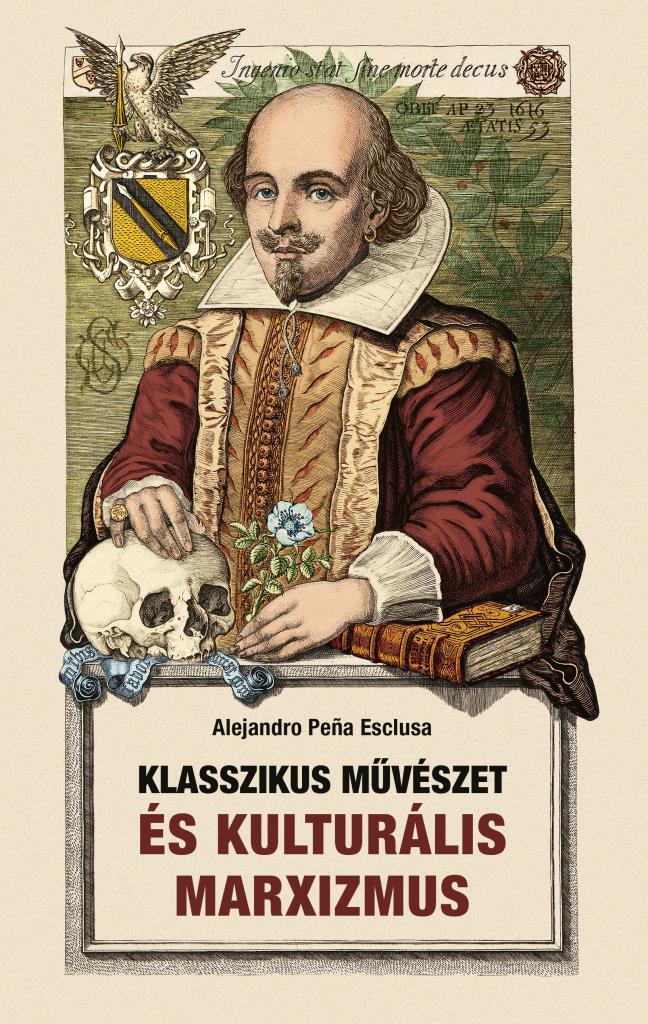

Classical Art and Cultural Marxism by Alejandro Peña Esclusa

The works of the geniuses of classical art (such as Shakespeare, Schiller, Cervantes, Dante, Mozart, Beethoven, Verdi, Da Vinci, Raphael, Brunelleschi, and many others) enrich the spirit, influence us with their beauty, glorify humanity’s finest qualities, promote virtues, and ultimately radiate optimism and faith in the future.

[…] They exalt the loving God, affirm that humanity was created in His image and likeness, and uphold immutable truths that apply to all of humanity, regardless of time and place. […] As time passed, and especially when I understood that the moral and cultural decline of the West was no accident but the result of a neo-Marxist plan, I began to appreciate the great classical works even more and value them as tools of resistance against this plan. […] During my long struggle against Venezuelan tyranny and Latin American Marxism, classical art served not only as a means to endure persecution, imprisonment, and exile but also as a source of inspiration to continue the fight even in my graying years.

Alejandro Peña Esclusa

The author of this book, Alejandro Peña Esclusa, was first politically and then financially incapacitated by Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez. He was deprived of his freedom, thrown into prison for political prisoners, and ultimately driven from his homeland, finding peace and safety in Europe as a Hungarian citizen. Yet he did not give up the fight for a free Venezuela. Throughout these ordeals, Alejandro Peña defended his identity with his Christian faith and the classical Western culture rooted in it, which he held before him as a shield.

Németh Zsolt

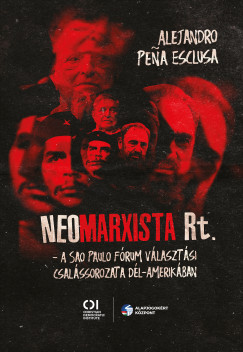

NEOMARXISTA RT. by Alejandro Peña Esclusa

The form of Latin American democracy as we know it today is soon to disappear, as a group of coup plotters, former resistance members, drug traffickers, and bribed individuals gathered around the São Paulo Forum and the Puebla Group have developed a sophisticated method that allows them to gain power through fraudulent means.

Alejandro Peña Esclusa’s study provides a detailed explanation of these mechanisms and how they operate. It offers an analysis that no researcher has conducted before, uncovering the connections behind the frauds perpetrated by the political left, not just in individual countries but across the entire region.

Peña Esclusa is one of the few who understands the São Paulo Forum in depth, having conducted extensive research on the subject for 28 years. He has paid a high price for this, facing persecution, imprisonment, and exile.

The Sao Paulo Forum’s Cultural Warfare by Alejandro Peña Esclusa

(Available here)

I am an eyewitness to how the most prosperous nation in Latin America—Venezuela—became in just 20 years the poorest, causing the largest exile in the history of our region, due to the policies of the Sao Paulo Forum. This was possible not only through the use of violence, but also primarily through a process of social engineering that could be implemented in any nation.

I am an eyewitness to how the most prosperous nation in Latin America—Venezuela—became in just 20 years the poorest, causing the largest exile in the history of our region, due to the policies of the Sao Paulo Forum. This was possible not only through the use of violence, but also primarily through a process of social engineering that could be implemented in any nation.

The Marxist cultural warfare, explained in detail in this book, is a subject that is of great importance to Hungarian readers, because it also affects their nation. This book explains why it has practically become a crime to defend the family, life from the moment of conception, territorial integrity, and patriotic values.

Moreover, the Sao Paulo Forum is expanding into Europe, through the illegal financing it provides to various parties in this region.

The story I describe here is the result of my long experience fighting the Sao Paulo Forum, which has cost me persecution, jail, and exile. My purpose is to help, so that Hungarians will never suffer the destruction that my country is going through.

Alejandro Peña Esclusa

The Curse of Popularity: Portraits, Ideologies, Programs From the Past and Present of Populism edited by Kristóf Heil and Bernadett Petri

The significant global rise of populism—which can mean, among other things, ideology, political behavior, style, strategy—is enlivening the scientific, political, and public discourses of our century, when it won the title of word of the year in 2017. Although the dominant tone and attitude of these discourses towards populism has always been strongly negative and hostile, the aim of the study volume The Curse of Popularity: Portraits, Ideologies, Programs From the Past and Present of Populism is to change this. The book edited by Kristóf Mihály Heil and Bernadett Petri highlights that populism is not as bad as we knew or thought until now.

From the eleven crisply written but factual chapters, we can learn about the conceptual difficulties of (political) populism, its history from the 19th century to the present day, and its current characteristics broken down into individual countries, parties, movements, and leaders. As a final conclusion, populism can be the highest expression of democracy, but it is at least the path leading to it, and by no means its opposite. Thus, instead of defending against being accused of populism, one should simply accept it and be proud of it. In this review, we call this new style or strategy that supports populism “hooray populism,” which—replacing post-liberalism—suggests the coming of a political zeitgeist in which the time for apologies is over.

As the subtitle of the volume indicates, the focus of the work is a comprehensive presentation of the past and present of populism, with some (necessary) overlaps between the chapters. Among other things, the origin of the Latin word populare, the early American and Russian populist movements, the appearance of populism and post-liberalism in Europe, populism in Latin America, Italy, and the United Kingdom, and Angela Merkel’s relationship to populism are discussed. Therefore, although the work is written with academic sophistication, its introductory and reinforcing nature makes it easy to read for those who are less familiar with the subject or with political science. Nevertheless, the volume is a fresh spot for those who want to deal more thoroughly with populism since the authors have replaced the sharply critical, hostile tone that dominates this topic with a striking and supportive, pro- or “hooray-populist” style.

The inherent novelty of the chapters dissolves the concrete unipolar approach of populism, which has characterized scientific, political, and public discourses until now. It highlights that the populism with which they like to label political actors—including the current Hungarian government and prime minister—is not a unique and modern phenomenon, it is not exclusively left-wing or right-wing, soft or hard, good or bad. Rather, it is an ideology, political behavior, style, and strategy, which has both positive and negative aspects, and which individual political parties, movements, and leaders can use profitably and to their liking. Populism’s aim is for the given political actor to gain popularity. And of course, who wouldn’t want that? Given that political success (especially in a democracy) requires popularity. In other words, all political actors use, for example, elements of populist rhetoric during their campaigns.

Despite this, some well-established political parties, movements and leaders are fondly given the populist stigma, accompanied by a strong negative connotation. They are applied to them as a kind of swear word or fighting phrase, which greatly spoils the taste of political success. Moreover, it can lead to political failure or loss of ground. And this is how popularity can turn from a blessing to a curse, to refer to the title of the volume. The new strategy proposed by the editors and the publisher offers an opportunity to get out of this vicious circle by the adoption of populism. After all, if populism is nothing more than the representation of the people’s interests, the will of the majority, then populism can also be the highest form of expression of democracy, so the stigmatized should—instead of making excuses for it—be proud of it (Szánthó, 2023: 7). Because of this included novel strategy or perception, the study volume The Curse of Popularity represents an important stage for thinking, writing, and talking about populism.